When Things Were Built To Last

How many things do you have that will last a lifetime… or more? A photo† essay.

No, I didn't buy her in 1901! But someone did! And she surely has lasted someone's lifetime in 123 years!

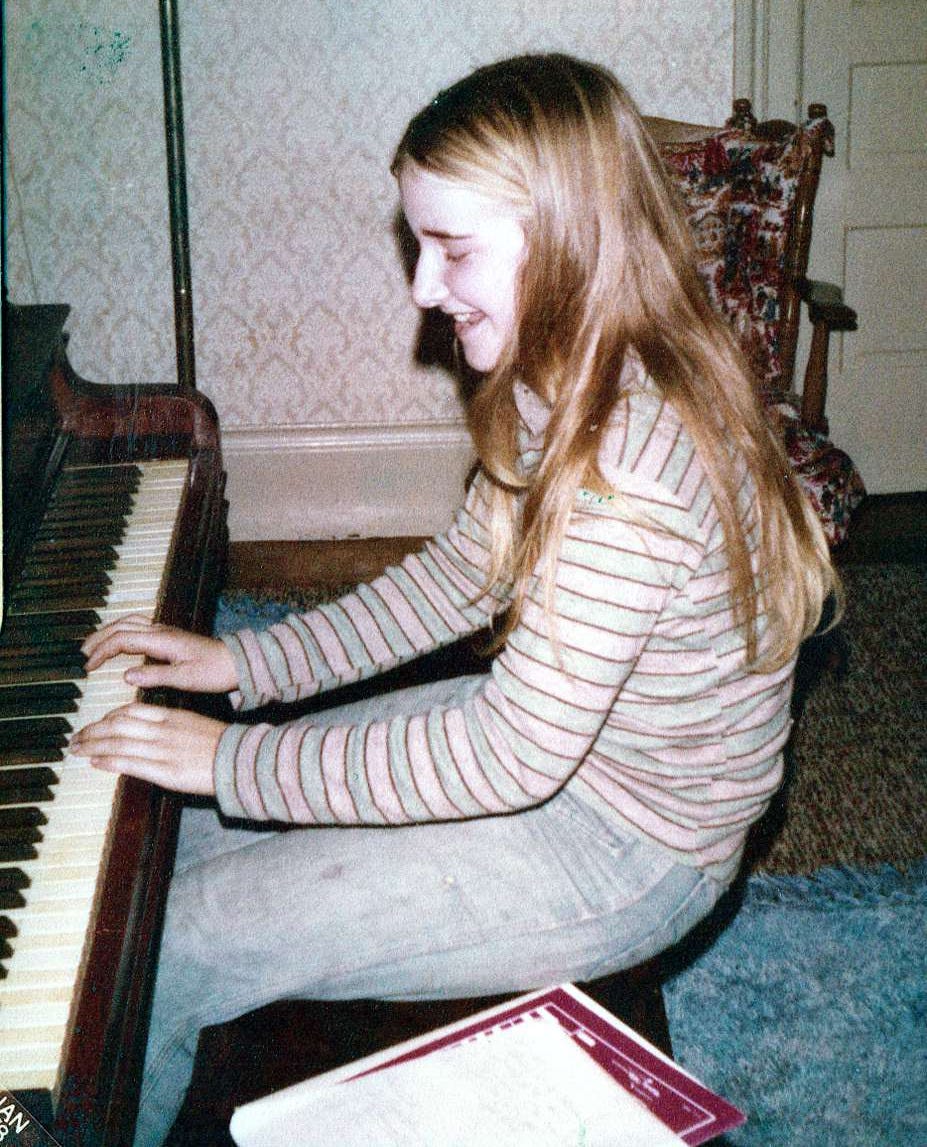

My Mom bought her for me when I was high school. There's a receipt taped inside, dated 15 May 1971, for $25. The person Mom bought her from had just re-done their porch steps, and insisted on a professional move, which cost another $50.

I enjoyed her a great deal while in band and chorus in high school. I also was in a “garage band” and put her to good use practising, although I had a portable Farfisa keyboard for gigs. I eventually moved away, winding up on the other side of the continent. After I moved out, my youngest sister took lessons and played her almost daily, also accompanying the high school chorus.

One day, I got a call from my other sister. "Andie [my niece] wants to take piano lessons. Can I borrow your piano for her?" Of course I agreed, happy that she would be used, as Gretchen had since moved away.

Fast forward some dozen years, to June 1998. I got another call from my sister. "Andie graduated, and just moved out. Come get this thing, or I'm hauling it to the dump!" she told me, laughing, but only half-joking.

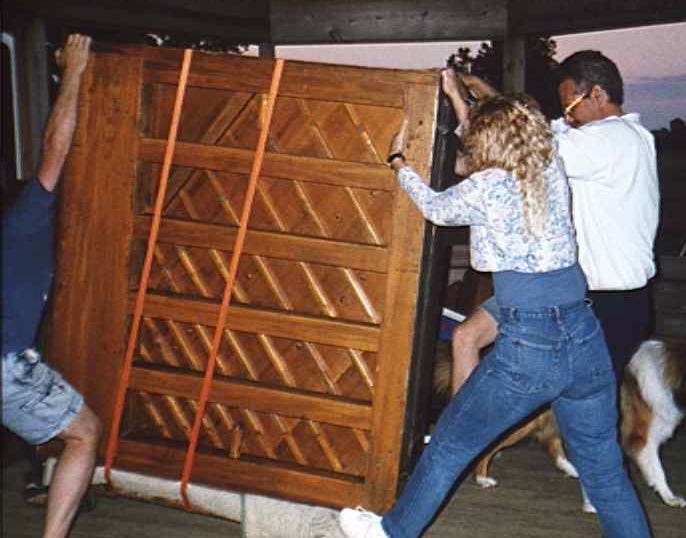

So, I bought a one-way plane ticket from Oregon to Michigan. Upon arrival, I bought a "beater" car for $500 and a simple flat-deck trailer. My two brothers and a brother-in-law and I each grabbed a corner, and we placed her on her back onto the trailer.

I knew the weather would be tricky, and didn't want her to get soaked, so I took her to a marina and had her shrink-wrapped! I wasn’t happy using single-use plastic this way, but at least she could survive any weather during the multi-day trip back to Oregon.

They seemed happy to do something unusual in the summer, a welcome break from wrapping boats for the winter.

We then drove her to Oregon, while the car slowly dissolved around us. The muffler fell off. The alternator quit working, so we had to stop using accessories and had to plug it in at night so it would start the next morning. Various other bits fell off here and there.

I was so glad for the shrink-wrapping — we hit some epic thunderstorms, so intense that we had to pull off the Interstate to sit out the storm beneath a viaduct! We could not see far enough ahead to drive!

On the way, my piano got to visit some interesting places, like the Badlands of South Dakota, Chief Crazy Horse’s statue (which in a stroke of luck, we were able to climb on the only day it was open to the public), Devil’s Tower, and the Columbia Gorge. Despite never having left Michigan for nearly a hundred years, she was becoming a well-travelled piano!

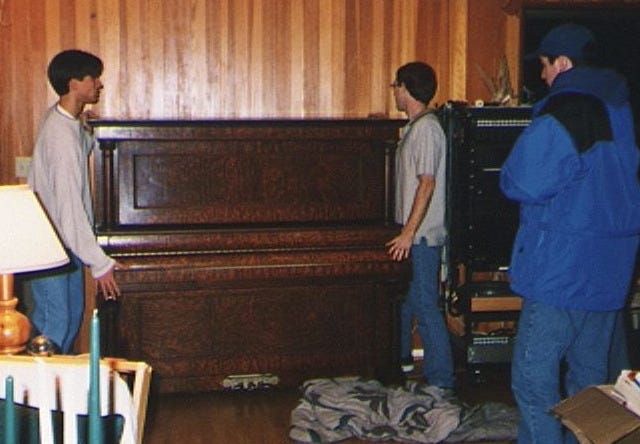

I had pre-arranged to deliver her to a piano restoration business in Oregon City. They unloaded her, and replaced all the bass strings, a number of rusty treble strings, all the felts, and all the hammers and some other small bits. They had her for months! But some $1,700 later, I had a piano that they told me was “like new” inside. That was a lot of money in 1998!

Finally, they delivered her to our house in West Linn.

It felt like getting back together with an old friend.

In 2004, after the second Dubya (s)election, I became disillusioned with the future of the US, thinking, "Things can't possibly get any worse!" (Boy, was I wrong!)

So I applied for immigration to Canada, and bought an older 43' semi-trailer for the move — turns out, that was cheaper than a moving van, and I could take my time packing and unpacking, and it doubled as a storage building after the move.

My ex and I packed almost everything from a 2,400 sqft house into that trailer by ourselves, but I was willing to pay professionals to move the piano. I found three Samoan brothers in the phone book — huge guys — and hired them to move her.

They were hilarious! They'd be jabbering in Samoan, until they saw one of us approaching, then they'd instantly switch to English. After loading her in the semi-trailer, one jumped down to the asphalt, shouting, "Look out Earth! Here I come!

She had a good life on Salt Spring Island, fitting nicely in a nook by the front door. I played her almost daily, and many guests and visitors enjoyed playing her, too.

Then in 2021, disaster struck. My wife (at the time) was diagnosed with a rare cancer. We could not find anyone nearby who was familiar with her particular cancer, which required expertise in a specialized sort of surgery.

So we moved to Bellingham, Washington, into her daughter’s guest room to be close to my wife’s cancer treatment. She was not in any condition to help, and I pretty much disposed of all our farm equipment, all my heavy tools, and most of our 2,900 sqft household.

But not the piano. Using levers, dollies, jacks, and ramps, I managed to move her all by myself from the living room (lead photo, above) into a sea can that we thought we could pay someone to bring to Bellingham.

In those COVID not-quite-over days, I couldn’t find a shipper willing to move our sea can to Bellingham, so I re-packed the piano (and everything else) into a 26’ U-Haul. I paid two helpers to move the piano into the U-Haul.

The piano went into another step-daughter’s house, where her daughter and husband enjoyed playing my piano. My ex survived a gruelling surgery, and decided she didn’t want to be married to me any more. Me and my piano moved back to Canada, to a temporary situation that I feared was almost the final resting spot for my piano!

The management was unwilling to have my piano in an accessible location, and they buried her in a barn, surrounded by heavy freezers and lots of other crap. It was dry there, but not temperature- or humidity-controlled, and I was worried about her.

When it came time to move, I bought a 120 sqft cargo trailer and moved what was left of my possessions into it, but the management said they could not free my piano from deep in the barn, because there was too much stuff in front of her!

I fretted and considered lawyers and police, but luckily, others there were willing to help me move her out from behind all the crap and freezers crammed full of heavy food. We used a fork-lift to put her in my new used trailer, and I dragged it two hours north, to another temporary location.

She lived in that trailer over the winter, with a dehumidifier running in the constant humidity of the West Coast. I would visit her now and then, pulling back the moving blankets and playing her until my fingers could no longer move in the cold.

Finally, this fall, I moved her some fifty kilometres across the Salish Sea via ferry, and friends here helped me load her into my humble 340 sqft cabin, where she enjoys a place of honour, and where I am able to play her nearly every day.

Why am I bothering you with this self-indulgant reminiscing?

Well, things don’t seem to last very long, these days. When I thought I was losing my piano to a nasty landlod, I visited thrift stores, where plastic and electronic keyboards that had barely been taken out of the box were on display for five cents on the dollar. At least a quarter of them were no longer working properly! Many were missing knobs or had cracked, broken, or scuffed plastic bits.

All this, at a time when traditional pianos are being sent to the dump at record rates!

I despair for a world where artifacts are “consumed” rather than enjoyed over multiple lifetimes, handed down over generations.

For some decades, I’ve been acutely aware of the coming Great Simplification. I purposely built up skills in troubleshooting, repair, and fixing things, thinking such would come in handy in a resource-constrained world.

Silly me! Nothing we are building today is intended to last more than ten years or so, and most is “intended” to barely last out the warranty — don’t want to compete with future sales! That washing machine or refrigerator your parents or grandparents used for fifty years? You’ll be lucky to get half that much from a modern one!

This is also how we are treating the Earth. Dig it up. Cut it down. Chop it up. Ship it from factory to factory. Use it up. Haul it to the dump. Throw it “away”. Well, we’re running out of “away” to throw things!

At least the sentient bonobos, canids, or cetaceans who might evolve after we’re gone will have lots of artifacts to examine — let’s hope they view such things as warning signs, rather than accomplishments to strive for!

Here’s what you can do to battle this toxic trend:

Buy things that are designed to last. It’s not always easy to make such a call. Choose things with a minimum of plastic parts, and with a minimum dependence on electronics.

Buy things with longer warranties. Warranty work is expensive, and companies that back their products better are more likely to build with long life and repairability in mind.

Buy things with minimal packaging, in cardboard and cellulose packing, rather than plastic and styrofoam.

Buy things made of natural materials that will gracefully degrade over time, rather than rapidly failing. Steel can be sharpened. Wood can be resurfaced and repaired. Plastic cracks and shatters. Electronics often emit the magic smoke that keeps them working.

Buy simple things over complicated ones. (See my previous article.) Simple electronics can often be repaired with a generic transistor and a soldering iron; complex ones often rely on custom integrated circuits with custom programming. When they stop making the custom part, kiss it’s long-life goodbye!

Best of all, don’t buy new things at all! Strive to buy older, repairable things, rather than feeding the beast with consumer demand.

The Great Simplification is coming. Avoid the rush, and simplify now!

†All text and photographs by Jan Steinman, Creative Commons licence. Please share and enjoy, just credit me and don’t claim you created it!

Enjoyed this and your previous piece quite a lot. Glad your piano has found its way to its final home!

Loved the story of that beautiful piano! Regarding 'simplification' I suggest Greer's original quote is more effective - "Collapse now and avoid the rush" as I find Nate Hagens notion of 'simplification' a euphemism which unfortunately downplays the severity of our predicament. As prof. Tainter identifies, civilization's don't simplify - they collapse. And this time it's global.